Master Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification: A Comprehensive Guide

If you have ever sat in a lecture hall at Tufts University, specifically within the Joyce Cummings Center, you know that the Computer Science department doesn’t just teach you how to code; it teaches you how to think. Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is a cornerstone of the introductory Artificial Intelligence (AI) curriculum, serving as a gateway into the world of probabilistic reasoning. While the “naive” label might suggest simplicity, the implementation of this algorithm—especially when dealing with real-world radar data—requires a nuanced understanding of both mathematics and software engineering.

In this guide, we will break down the mechanics of the Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification approach. We’ll explore the underlying Bayes’ Theorem, dive into the specifics of the famous “Birds vs. Airplanes” assignment, and provide the technical insights you need to excel in this rigorous course. Whether you are a Jumbo currently enrolled in CS131 or a lifelong learner curious about generative models, this deep dive is for you.

What is Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification?

At its core, Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification refers to the study and implementation of a probabilistic classifier based on Bayes’ Theorem.1 In the context of the Tufts AI course, students are challenged to move beyond black-box libraries like Scikit-learn and build these models from the ground up using Python. This “from scratch” philosophy ensures that students grasp the mechanics of how data transforms into a prediction

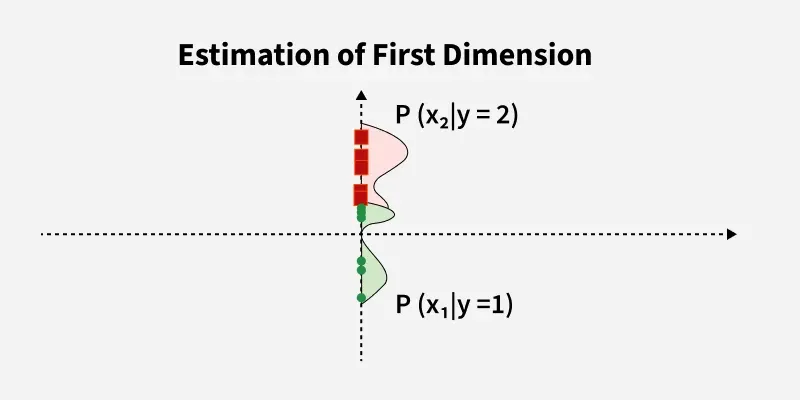

The algorithm is a generative model.2 Unlike discriminative models that simply learn the boundary between classes, a generative model learns the distribution of the data itself.3 By understanding the patterns that define a specific category, the model can then calculate the probability that a new, unseen data point belongs to that category.4 In the CS131 curriculum, this is often applied to classification tasks where the input features are assumed to be independent—the “naive” assumption that makes the math manageable yet surprisingly effective.5

The Mathematical Foundation: Bayes’ Theorem

To master Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification, you must first master the equation that started it all. Named after Thomas Bayes, this theorem provides a way to update the probability of a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available.6

The formula is expressed as:

Where:

-

$P(C|X)$ (Posterior): The probability that the data 7$X$ belongs to class 8$C$ after seeing the evidence.9

-

$P(X|C)$ (Likelihood): The probability of observing features 10$X$ given that we know the class is 11$C$.12

-

$P(C)$ (Prior): Our initial belief about how common class 13$C$ is in the world.14

-

$P(X)$ (Evidence): The total probability of the features occurring across all classes.

In a typical classification task, we compare the posterior probabilities for all possible classes and choose the one with the highest value.15 This is known as the Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) decision rule.

Why Is It Called “Naive”?

The “Naive” in Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification comes from a bold simplification. In the real world, features are often correlated.16 For example, if you are looking at radar data for an airplane, its “speed” and “altitude” are likely related. A “non-naive” model would try to calculate the joint probability of all features combined, which becomes computationally explosive as you add more variables.

The Naive Bayes classifier assumes that all features are conditionally independent given the class. Mathematically, this means:

By treating each feature as a solo act, we only need to calculate individual probabilities and multiply them together. While this assumption is almost always false in reality, the classifier remains remarkably robust.17 It often outperforms more complex algorithms, especially when training data is scarce or when the features are high-dimensional.

The Tufts CS131 Assignment: The Radar Challenge

One of the most memorable parts of the Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification module is the programming assignment involving radar tracks. Students are given a dataset containing measurements of unidentified flying objects.18 The goal is to classify these objects into one of two categories: Birds (B) or Airplanes (A).19

Working with Radar Data

The data typically consists of time-series measurements, such as speed or signal strength, sampled at specific intervals (e.g., 1s sampling for 600s).20 Implementing Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification for this task involves several hurdles:

-

Handling Missing Data (NaNs): Real-world radar isn’t perfect. Dropped signals appear as “NaN” values in the dataset. Students must decide whether to ignore these points, interpolate them, or treat the “missingness” as a feature itself.

-

Continuous vs. Discrete Features: Radar speed is a continuous variable. In CS131, students might use a Gaussian Naive Bayes approach, assuming the speeds follow a bell curve, or they might “bin” the data into discrete categories.

-

Feature Engineering: To get the “Bonus” points often offered in the course, students must extract additional features—like the variance of speed or the rate of climb—to help the model distinguish between the erratic flight of a bird and the steady path of a plane.

Practical Implementation: Python from Scratch

When you sit down to write your code for Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification, you’ll likely use Python. While it’s tempting to import GaussianNB from sklearn, the Tufts curriculum demands that you implement the logic yourself. This usually involves three main phases:

1. The Training Phase

During training, your script calculates the Priors and Likelihoods from the training set.

-

Priors: What percentage of the total tracks are birds vs. airplanes?

-

Likelihoods: For each class, what is the mean and standard deviation of the features (if using Gaussian) or the frequency of specific values (if using Multinomial/Bernoulli)?

2. The Testing Phase

Once the model is “trained” (which, in Naive Bayes, is really just a matter of storing these calculated constants), you apply it to new data.21 For every unidentified track, you calculate the product of the prior and all the likelihoods for each class.

3. Log Probabilities to the Rescue

A common pitfall in Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is the “underflow” problem. Because probabilities are decimals between 0 and 1, multiplying dozens of them together results in a number so tiny that computers round it down to zero.

To fix this, we use the Log Likelihood. Instead of multiplying probabilities, we add their logarithms:

This keeps the numbers at a manageable scale and is a standard trick in any AI engineer’s toolkit.

Overcoming the Zero-Frequency Problem

Another critical concept in Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is Laplace Smoothing.22 Imagine you are building a text classifier and you encounter a word in the test set that never appeared in your training data for “Category A.

Without smoothing, the probability $P(\text{word} | \text{Category A})$ would be 0. Since we are multiplying probabilities, that single zero would cancel out everything else, making the entire posterior probability 0. Laplace smoothing adds a small “pseudocount” (usually 1 or a small alpha) to every feature count, ensuring that no probability is ever exactly zero.23 This “safety net” is vital for the model’s reliability.

Why Tufts Students Love (and Hate) This Topic

Students often find Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification to be one of the more satisfying topics because the results are immediate. You can take a messy text file of radar coordinates and, within a few lines of math, accurately predict what is in the sky.

However, the challenge lies in the details. Cross-validation (like using N-Folds) is often required to ensure the model isn’t just “memorizing” the training data but is actually learning to generalize. Debugging a probabilistic model is also famously difficult—if your accuracy is stuck at 50%, is it because of a math error, a data parsing bug, or a fundamental misunderstanding of the independence assumption?

Real-World Applications Beyond Tufts

While the “Birds vs. Airplanes” project is a classroom staple, the principles of Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification power many systems we use daily:

-

Spam Filtering: This is the classic use case. By looking at the “likelihood” of words like “Free,” “Winner,” and “Urgent” appearing in spam vs. legitimate emails, your inbox stays clean.

-

Sentiment Analysis: Companies use Naive Bayes to scan thousands of social media posts to determine if the general public sentiment toward their brand is positive or negative.24

-

Medical Diagnosis: By treating symptoms as features, a Bayesian model can help predict the likelihood of a disease given a patient’s profile.25

-

Document Classification: Whether it’s sorting news articles into “Sports” and “Politics” or organizing legal documents, the speed of Naive Bayes makes it ideal for large-scale text processing.26

Best Practices for Success in CS131

If you are preparing for your midterms or working on the assignment, keep these tips in mind for Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification:

-

Vectorize Your Math: Use NumPy. While you can write loops to calculate probabilities, NumPy’s vectorized operations are faster and less prone to indexing errors.

-

Visualize the Data: Before you code, plot your features. If you see that “Speed” for airplanes and birds overlaps significantly, you’ll know that speed alone won’t be enough for high accuracy.

-

Document Your Extensions: If you implement the bonus features (like handling NaNs or adding new radar metrics), explain your reasoning in your README. The TAs at Tufts value the “why” as much as the “how.”

-

Check Your Priors: Don’t assume the classes are 50/50. If the dataset has 80% planes, your model should reflect that initial bias.

Conclusion

The study of Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is more than just a programming exercise; it is an introduction to the elegant simplicity of Bayesian thinking. By acknowledging that our knowledge is always probabilistic and subject to update, we build AI systems that are both efficient and interpretable.

Whether you are navigating the complexities of radar tracks or building the next great spam filter, the foundation you build in CS131 will serve you throughout your career in technology. Remember, the “naive” assumption isn’t a bug—it’s a feature that allows us to find signal in the noise.

Would you like me to provide a Python code template for a basic Naive Bayes implementation from scratch?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the main difference between Multinomial and Gaussian Naive Bayes?

Multinomial Naive Bayes is typically used for discrete data, such as word counts in text classification.27 It models the probability based on the frequency of occurrences.28 Gaussian Naive Bayes is used for continuous data (like the radar speed in Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification), where it assumes the features follow a normal (Gaussian) distribution.29

2. Can Naive Bayes handle missing values?

Yes. One of the strengths of Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is that it handles missing values gracefully. If a specific feature is missing for a data point, you can simply omit that feature’s likelihood from the product calculation for that specific instance.

3. Why is Laplace smoothing used in text classification?

Laplace smoothing prevents the “Zero Probability” problem.30 If a word appears in the test set but wasn’t in the training set for a specific class, the probability becomes zero. Adding a small constant to all counts ensures the model can still make a prediction even when it encounters unfamiliar features.3

4. INaive Bayes still relevant in the age of Deep Learning?

Absolutely. While Deep Learning excels at complex patterns, Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification is significantly faster, requires far less data, and is much easier to debug. It is often used as a “baseline” model to see if a more complex neural network is even necessary.32

5. How does N-Fold Cross-Validation work in the CS131 assignment?

In N-Fold Cross-Validation, you split your data into $N$ equal parts (folds). You train the model on $N-1$ folds and test it on the remaining fold. You repeat this $N$ times, ensuring every data point is used for testing exactly once. This gives a much more accurate representation of how the Tufts CS131 Naive Bayesian Classification model will perform on truly unseen data.